The Was a German School of Art and Design That Operated in the Early Twentieth Century

| UNESCO World Heritage Site | |

|---|---|

The Bauhaus building in Dessau was designed past Walter Gropius. It was the longest serving of the three Bauhaus locations (1925–1932). | |

| Location | Federal republic of germany |

| Criteria | Cultural: 2, iv, vi |

| Reference | 729 |

| Inscription | 1996 (20th Session) |

| Surface area | 8.1614 |

| Buffer zone | 59.26 |

| Weimar Dessau Bernau | |

The Staatliches Bauhaus (German: [ˈʃtaːtlɪçəs ˈbaʊˌhaʊs] ( ![]() heed )), commonly known as the Bauhaus (German for 'edifice house'), was a German art school operational from 1919 to 1933 that combined crafts and the fine arts.[ane] The school became famous for its approach to pattern, which attempted to unify the principles of mass production with private artistic vision and strove to combine aesthetics with everyday function.[ane]

heed )), commonly known as the Bauhaus (German for 'edifice house'), was a German art school operational from 1919 to 1933 that combined crafts and the fine arts.[ane] The school became famous for its approach to pattern, which attempted to unify the principles of mass production with private artistic vision and strove to combine aesthetics with everyday function.[ane]

The Bauhaus was founded by architect Walter Gropius in Weimar. Information technology was grounded in the idea of creating a Gesamtkunstwerk ("comprehensive artwork") in which all the arts would eventually be brought together. The Bauhaus style afterwards became one of the most influential currents in mod design, modernist architecture and fine art, design, and architectural didactics.[2] The Bauhaus motility had a profound influence upon subsequent developments in art, compages, graphic design, interior design, industrial pattern, and typography.[three] Staff at the Bauhaus included prominent artists such as Paul Klee, Wassily Kandinsky, and László Moholy-Nagy at various points.

The school existed in three German cities—Weimar, from 1919 to 1925; Dessau, from 1925 to 1932; and Berlin, from 1932 to 1933—under three different architect-directors: Walter Gropius from 1919 to 1928; Hannes Meyer from 1928 to 1930; and Ludwig Mies van der Rohe from 1930 until 1933, when the school was closed by its own leadership under force per unit area from the Nazi regime, having been painted as a centre of communist intellectualism. Although the schoolhouse was airtight, the staff continued to spread its idealistic precepts equally they left Germany and emigrated all over the world.[4]

The changes of venue and leadership resulted in a constant shifting of focus, technique, instructors, and politics. For example, the pottery shop was discontinued when the schoolhouse moved from Weimar to Dessau, even though information technology had been an important revenue source; when Mies van der Rohe took over the school in 1930, he transformed information technology into a private schoolhouse and would non allow any supporters of Hannes Meyer to attend information technology.

Pattern style [edit]

The Bauhaus manner tends to feature simple geometric shapes like rectangles and spheres, without elaborate decorations. Buildings, furniture, and fonts often characteristic rounded corners and sometimes rounded walls. Other buildings are characterized past rectangular features, for instance protruding balconies with apartment, chunky railings facing the street, and long banks of windows. Article of furniture oftentimes uses chrome metallic pipes that bend at corners.

Bauhaus and German language modernism [edit]

After Germany's defeat in World War I and the institution of the Weimar Republic, a renewed liberal spirit allowed an upsurge of radical experimentation in all the arts, which had been suppressed by the old regime. Many Germans of left-wing views were influenced by the cultural experimentation that followed the Russian Revolution, such as constructivism. Such influences can exist overstated: Gropius did not share these radical views, and said that Bauhaus was entirely apolitical.[5] But as of import was the influence of the 19th-century English designer William Morris (1834–1896), who had argued that art should meet the needs of lodge and that there should exist no distinction betwixt form and function.[6] Thus, the Bauhaus style, also known every bit the International Style, was marked by the absence of ornamentation and by harmony between the role of an object or a building and its design.

However, the near important influence on Bauhaus was modernism, a cultural move whose origins lay as early equally the 1880s, and which had already fabricated its presence felt in Germany before the Earth War, despite the prevailing conservatism. The blueprint innovations commonly associated with Gropius and the Bauhaus—the radically simplified forms, the rationality and functionality, and the idea that mass production was reconcilable with the private creative spirit—were already partly developed in Germany earlier the Bauhaus was founded. The German language national designers' organization Deutscher Werkbund was formed in 1907 past Hermann Muthesius to harness the new potentials of mass production, with a heed towards preserving Federal republic of germany's economic competitiveness with England. In its starting time vii years, the Werkbund came to exist regarded as the authoritative body on questions of design in Germany, and was copied in other countries. Many fundamental questions of adroitness versus mass product, the relationship of usefulness and beauty, the applied purpose of formal beauty in a commonplace object, and whether or non a unmarried proper form could exist, were argued out amid its 1,870 members (by 1914).

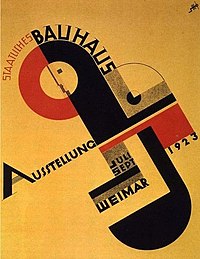

Poster for the Bauhausaustellung (1923)

High german architectural modernism was known every bit Neues Bauen. Beginning in June 1907, Peter Behrens' pioneering industrial design piece of work for the German electric visitor AEG successfully integrated fine art and mass production on a large scale. He designed consumer products, standardized parts, created make clean-lined designs for the company's graphics, developed a consistent corporate identity, built the modernist landmark AEG Turbine Factory, and made full use of newly developed materials such every bit poured physical and exposed steel. Behrens was a founding member of the Werkbund, and both Walter Gropius and Adolf Meyer worked for him in this period.

The Bauhaus was founded at a fourth dimension when the German zeitgeist had turned from emotional Expressionism to the matter-of-fact New Objectivity. An entire group of working architects, including Erich Mendelsohn, Bruno Taut and Hans Poelzig, turned away from fanciful experimentation and towards rational, functional, sometimes standardized building. Beyond the Bauhaus, many other meaning German language-speaking architects in the 1920s responded to the same aesthetic issues and fabric possibilities equally the school. They too responded to the promise of a "minimal home" written into the new Weimar Constitution. Ernst May, Bruno Taut and Martin Wagner, among others, congenital large housing blocks in Frankfurt and Berlin. The acceptance of modernist design into everyday life was the subject field of publicity campaigns, well-attended public exhibitions like the Weissenhof Estate, films, and sometimes tearing public argue.

Bauhaus and Vkhutemas [edit]

The Vkhutemas, the Russian state art and technical school founded in 1920 in Moscow, has been compared to Bauhaus. Founded a year later the Bauhaus schoolhouse, Vkhutemas has close parallels to the German language Bauhaus in its intent, organization and telescopic. The two schools were the first to train artist-designers in a modern manner.[7] Both schools were state-sponsored initiatives to merge traditional arts and crafts with modern engineering science, with a bones class in aesthetic principles, courses in color theory, industrial pattern, and compages.[7] Vkhutemas was a larger school than the Bauhaus,[viii] but it was less publicised exterior the Soviet Union and consequently, is less familiar in the West.[9]

With the internationalism of modern architecture and design, there were many exchanges between the Vkhutemas and the Bauhaus.[10] The 2nd Bauhaus director Hannes Meyer attempted to organise an exchange between the two schools, while Hinnerk Scheper of the Bauhaus collaborated with diverse Vkhutein members on the employ of colour in compages. In improver, El Lissitzky's book Russia: an Architecture for World Revolution published in High german in 1930 featured several illustrations of Vkhutemas/Vkhutein projects in that location.

History of the Bauhaus [edit]

Weimar [edit]

The school was founded by Walter Gropius in Weimar on 1 April 1919,[11] as a merger of the Grand-Ducal Saxon Academy of Fine Fine art and the Grand Ducal Saxon School of Arts and Crafts for a newly affiliated compages department.[12] Its roots lay in the craft school founded past the Chiliad Duke of Saxe-Weimar-Eisenach in 1906, and directed past Belgian Art Nouveau architect Henry van de Velde.[13] When van de Velde was forced to resign in 1915 because he was Belgian, he suggested Gropius, Hermann Obrist, and August Endell as possible successors. In 1919, later delays caused by World War I and a lengthy fence over who should caput the institution and the socio-economic meanings of a reconciliation of the fine arts and the applied arts (an issue which remained a defining one throughout the schoolhouse's existence), Gropius was made the director of a new institution integrating the 2 called the Bauhaus.[14] In the pamphlet for an Apr 1919 exhibition entitled Exhibition of Unknown Architects, Gropius, still very much under the influence of William Morris and the British Arts and Crafts Motility, proclaimed his goal equally being "to create a new guild of craftsmen, without the class distinctions which raise an arrogant barrier between craftsman and artist." Gropius'due south neologism Bauhaus references both edifice and the Bauhütte, a premodern social club of stonemasons.[fifteen] The early intention was for the Bauhaus to be a combined architecture school, crafts schoolhouse, and academy of the arts. Swiss painter Johannes Itten, German-American painter Lyonel Feininger, and German language sculptor Gerhard Marcks, along with Gropius, comprised the faculty of the Bauhaus in 1919. Past the following year their ranks had grown to include German language painter, sculptor, and designer Oskar Schlemmer who headed the theatre workshop, and Swiss painter Paul Klee, joined in 1922 past Russian painter Wassily Kandinsky. A tumultuous yr at the Bauhaus, 1922 also saw the move of Dutch painter Theo van Doesburg to Weimar to promote De Stijl ("The Mode"), and a visit to the Bauhaus past Russian Constructivist artist and architect El Lissitzky.[16]

From 1919 to 1922 the school was shaped by the pedagogical and aesthetic ideas of Johannes Itten, who taught the Vorkurs or "preliminary course" that was the introduction to the ideas of the Bauhaus.[14] Itten was heavily influenced in his teaching by the ideas of Franz Cižek and Friedrich Wilhelm Baronial Fröbel. He was as well influenced in respect to aesthetics past the work of the Der Blaue Reiter group in Munich, as well equally the work of Austrian Expressionist Oskar Kokoschka. The influence of German Expressionism favoured past Itten was analogous in some ways to the fine arts side of the ongoing argue. This influence culminated with the addition of Der Blaue Reiter founding member Wassily Kandinsky to the faculty and ended when Itten resigned in late 1923. Itten was replaced by the Hungarian designer László Moholy-Nagy, who rewrote the Vorkurs with a leaning towards the New Objectivity favoured by Gropius, which was analogous in some ways to the applied arts side of the contend. Although this shift was an important one, information technology did non stand for a radical intermission from the past so much as a small step in a broader, more gradual socio-economical move that had been going on at to the lowest degree since 1907, when van de Velde had argued for a craft basis for design while Hermann Muthesius had begun implementing industrial prototypes.[xvi]

Gropius was not necessarily against Expressionism, and in fact, himself in the aforementioned 1919 pamphlet proclaiming this "new guild of craftsmen, without the course snobbery", described "painting and sculpture ascent to heaven out of the hands of a million craftsmen, the crystal symbol of the new faith of the future." By 1923, yet, Gropius was no longer evoking images of soaring Romanesque cathedrals and the craft-driven aesthetic of the "Völkisch movement", instead declaring "we desire an compages adapted to our globe of machines, radios and fast cars."[17] Gropius argued that a new period of history had begun with the end of the war. He wanted to create a new architectural style to reverberate this new era. His style in compages and consumer goods was to exist functional, cheap and consistent with mass product. To these ends, Gropius wanted to reunite fine art and arts and crafts to get in at high-end functional products with artistic merit. The Bauhaus issued a magazine called Bauhaus and a series of books chosen "Bauhausbücher". Since the Weimar Republic lacked the number of raw materials bachelor to the United States and Great Britain, it had to rely on the proficiency of a skilled labour force and an power to export innovative and high-quality appurtenances. Therefore, designers were needed and then was a new type of art teaching. The school'southward philosophy stated that the creative person should be trained to work with the manufacture.[xviii] [19]

Weimar was in the German state of Thuringia, and the Bauhaus schoolhouse received state support from the Social Democrat-controlled Thuringian state government. The school in Weimar experienced political pressure from conservative circles in Thuringian politics, increasingly so after 1923 as political tension rose. Ane condition placed on the Bauhaus in this new political environs was the exhibition of work undertaken at the schoolhouse. This status was met in 1923 with the Bauhaus' exhibition of the experimental Haus am Horn.[twenty] The Ministry of Instruction placed the staff on six-month contracts and cutting the school's funding in half. The Bauhaus issued a printing release on 26 December 1924, setting the closure of the schoolhouse for the cease of March 1925.[21] [22] At this point it had already been looking for alternative sources of funding. After the Bauhaus moved to Dessau, a school of industrial pattern with teachers and staff less combative to the conservative political regime remained in Weimar. This schoolhouse was somewhen known as the Technical University of Architecture and Civil Engineering, and in 1996 changed its name to Bauhaus-University Weimar.

Chair past Erich Dieckmann, 1925

Dessau [edit]

The Bauhaus moved to Dessau in 1925 and new facilities there were inaugurated in late 1926. Gropius's design for the Dessau facilities was a return to the futuristic Gropius of 1914 that had more in mutual with the International manner lines of the Fagus Factory than the stripped down Neo-classical of the Werkbund pavilion or the Völkisch Sommerfeld House.[23] During the Dessau years, there was a remarkable change in direction for the school. According to Elaine Hoffman, Gropius had approached the Dutch architect Mart Stam to run the newly founded architecture program, and when Stam declined the position, Gropius turned to Stam's friend and colleague in the ABC grouping, Hannes Meyer.

Meyer became director when Gropius resigned in February 1928,[1] and brought the Bauhaus its two most significant building commissions, both of which still be: v apartment buildings in the metropolis of Dessau, and the Bundesschule des Allgemeinen Deutschen Gewerkschaftsbundes (ADGB Trade Union Schoolhouse) in Bernau bei Berlin. Meyer favoured measurements and calculations in his presentations to clients, along with the use of off-the-shelf architectural components to reduce costs. This approach proved bonny to potential clients. The schoolhouse turned its first profit under his leadership in 1929.

But Meyer also generated a groovy deal of conflict. As a radical functionalist, he had no patience with the artful plan and forced the resignations of Herbert Bayer, Marcel Breuer, and other long-time instructors. Fifty-fifty though Meyer shifted the orientation of the school further to the left than it had been under Gropius, he didn't want the schoolhouse to become a tool of left-wing party politics. He prevented the germination of a student communist jail cell, and in the increasingly dangerous political atmosphere, this became a threat to the existence of the Dessau school. Dessau mayor Fritz Hesse fired him in the summer of 1930.[24] The Dessau urban center quango attempted to convince Gropius to render equally head of the school, simply Gropius instead suggested Ludwig Mies van der Rohe. Mies was appointed in 1930 and immediately interviewed each pupil, dismissing those that he deemed uncommitted. He halted the school's manufacture of goods so that the schoolhouse could focus on instruction, and appointed no new kinesthesia other than his close confidant Lilly Reich. Past 1931, the Nazi Party was becoming more influential in German politics. When it gained control of the Dessau city quango, it moved to shut the school.[25]

Berlin [edit]

In late 1932, Mies rented a derelict factory in Berlin (Birkbusch Street 49) to use as the new Bauhaus with his own money. The students and kinesthesia rehabilitated the building, painting the interior white. The school operated for 10 months without further interference from the Nazi Party. In 1933, the Gestapo closed downwardly the Berlin school. Mies protested the decision, somewhen speaking to the head of the Gestapo, who agreed to let the schoolhouse to re-open. However, soon after receiving a alphabetic character permitting the opening of the Bauhaus, Mies and the other faculty agreed to voluntarily close downward the school[ when? ].[25]

Although neither the Nazi Party nor Adolf Hitler had a cohesive architectural policy before they came to ability in 1933, Nazi writers like Wilhelm Frick and Alfred Rosenberg had already labelled the Bauhaus "un-German language" and criticized its modernist styles, deliberately generating public controversy over issues like flat roofs. Increasingly through the early 1930s, they characterized the Bauhaus as a front for communists and social liberals. Indeed, when Meyer was fired in 1930, a number of communist students loyal to him moved to the Soviet Union.

Even before the Nazis came to power, political force per unit area on Bauhaus had increased. The Nazi movement, from nearly the start, denounced the Bauhaus for its "degenerate art", and the Nazi regime was adamant to fissure down on what it saw as the foreign, probably Jewish, influences of "cosmopolitan modernism".[1] Despite Gropius's protestations that as a war veteran and a patriot his work had no subversive political intent, the Berlin Bauhaus was pressured to shut in April 1933. Emigrants did succeed, however, in spreading the concepts of the Bauhaus to other countries, including the "New Bauhaus" of Chicago:[26] Mies decided to emigrate to the United states of america for the directorship of the School of Architecture at the Armour Institute (now Illinois Institute of Engineering) in Chicago and to seek building commissions.[a] The unproblematic engineering-oriented functionalism of stripped-down modernism, withal, did lead to some Bauhaus influences living on in Nazi Germany. When Hitler'due south main engineer, Fritz Todt, began opening the new autobahns (highways) in 1935, many of the bridges and service stations were "assuming examples of modernism", and among those submitting designs was Mies van der Rohe.[27]

Architectural output [edit]

The paradox of the early Bauhaus was that, although its manifesto proclaimed that the aim of all creative activity was building,[28] the school did not offer classes in compages until 1927. During the years under Gropius (1919–1927), he and his partner Adolf Meyer observed no real distinction between the output of his architectural office and the school. So the built output of Bauhaus architecture in these years is the output of Gropius: the Sommerfeld firm in Berlin, the Otte house in Berlin, the Auerbach house in Jena, and the competition design for the Chicago Tribune Tower, which brought the school much attention. The definitive 1926 Bauhaus building in Dessau is as well attributed to Gropius. Apart from contributions to the 1923 Haus am Horn, student architectural work amounted to un-built projects, interior finishes, and craft work similar cabinets, chairs and pottery.

In the next two years under Meyer, the architectural focus shifted away from aesthetics and towards functionality. At that place were major commissions: one from the urban center of Dessau for five tightly designed "Laubenganghäuser" (apartment buildings with balustrade access), which are still in utilise today, and another for the Bundesschule des Allgemeinen Deutschen Gewerkschaftsbundes (ADGB Trade Union Schoolhouse) in Bernau bei Berlin. Meyer'due south approach was to research users' needs and scientifically develop the pattern solution.

Mies van der Rohe repudiated Meyer'south politics, his supporters, and his architectural approach. As opposed to Gropius'due south "study of essentials", and Meyer's research into user requirements, Mies advocated a "spatial implementation of intellectual decisions", which effectively meant an adoption of his own aesthetics. Neither Mies van der Rohe nor his Bauhaus students saw any projects built during the 1930s.

The popular conception of the Bauhaus as the source of extensive Weimar-era working housing is not authentic. Ii projects, the apartment building project in Dessau and the Törten row housing also in Dessau, autumn in that category, only developing worker housing was not the commencement priority of Gropius nor Mies. It was the Bauhaus contemporaries Bruno Taut, Hans Poelzig and particularly Ernst May, as the city architects of Berlin, Dresden and Frankfurt respectively, who are rightfully credited with the thousands of socially progressive housing units built in Weimar Germany. The housing Taut built in south-due west Berlin during the 1920s, shut to the U-Bahn stop Onkel Toms Hütte, is still occupied.

Impact [edit]

The Bauhaus had a major impact on fine art and architecture trends in Western Europe, Canada, the United States and Israel in the decades post-obit its demise, every bit many of the artists involved fled, or were exiled by the Nazi regime. Tel Aviv in 2004 was named to the list of world heritage sites by the UN due to its abundance of Bauhaus compages;[29] [30] it had some 4,000 Bauhaus buildings erected from 1933 onwards.

In 1928, the Hungarian painter Alexander Bortnyik founded a school of design in Budapest called Műhely,[31] which ways "the studio".[32] Located on the 7th floor of a firm on Nagymezo Street,[32] it was meant to be the Hungarian equivalent to the Bauhaus.[33] The literature sometimes refers to it—in an oversimplified manner—as "the Budapest Bauhaus".[34] Bortnyik was a cracking admirer of László Moholy-Nagy and had met Walter Gropius in Weimar between 1923 and 1925.[35] Moholy-Nagy himself taught at the Miihely. Victor Vasarely, a pioneer of Op Art, studied at this schoolhouse before establishing in Paris in 1930.[36]

Walter Gropius, Marcel Breuer, and Moholy-Nagy re-assembled in Great britain during the mid 1930s and lived and worked in the Isokon housing development in Lawn Road in London before the state of war caught upwards with them. Gropius and Breuer went on to teach at the Harvard Graduate School of Blueprint and worked together before their professional split up. Their collaboration produced, among other projects, the Aluminum Metropolis Terrace in New Kensington, Pennsylvania and the Alan I W Frank Firm in Pittsburg. The Harvard School was enormously influential in America in the late 1920s and early 1930s, producing such students equally Philip Johnson, I. One thousand. Pei, Lawrence Halprin and Paul Rudolph, among many others.

In the late 1930s, Mies van der Rohe re-settled in Chicago, enjoyed the sponsorship of the influential Philip Johnson, and became 1 of the world'south pre-eminent architects. Moholy-Nagy too went to Chicago and founded the New Bauhaus school under the sponsorship of industrialist and philanthropist Walter Paepcke. This school became the Plant of Pattern, part of the Illinois Plant of Technology. Printmaker and painter Werner Drewes was also largely responsible for bringing the Bauhaus aesthetic to America and taught at both Columbia University and Washington Academy in St. Louis. Herbert Bayer, sponsored past Paepcke, moved to Aspen, Colorado in support of Paepcke's Aspen projects at the Aspen Establish. In 1953, Max Beak, together with Inge Aicher-Scholl and Otl Aicher, founded the Ulm School of Blueprint (High german: Hochschule für Gestaltung – HfG Ulm) in Ulm, Germany, a design school in the tradition of the Bauhaus. The school is notable for its inclusion of semiotics as a subject. The school airtight in 1968, simply the "Ulm Model" concept continues to influence international design education.[37] Some other series of projects at the school were the Bauhaus typefaces, mostly realized in the decades afterward.

The influence of the Bauhaus on design education was pregnant. One of the primary objectives of the Bauhaus was to unify art, craft, and technology, and this approach was incorporated into the curriculum of the Bauhaus. The structure of the Bauhaus Vorkurs (preliminary grade) reflected a pragmatic approach to integrating theory and application. In their beginning yr, students learnt the basic elements and principles of design and colour theory, and experimented with a range of materials and processes.[38] [39] This approach to blueprint didactics became a common feature of architectural and design school in many countries. For example, the Shillito Design School in Sydney stands as a unique link between Australia and the Bauhaus. The colour and design syllabus of the Shillito Pattern School was firmly underpinned by the theories and ideologies of the Bauhaus. Its first year foundational course mimicked the Vorkurs and focused on the elements and principles of design plus colour theory and application. The founder of the school, Phyllis Shillito, which opened in 1962 and closed in 1980, firmly believed that "A student who has mastered the basic principles of design, can design anything from a clothes to a kitchen stove".[xl] In U.k., largely under the influence of painter and teacher William Johnstone, Basic Design, a Bauhaus-influenced art foundation course, was introduced at Camberwell School of Art and the Cardinal School of Art and Design, whence it spread to all art schools in the country, becoming universal by the early 1960s.

I of the virtually important contributions of the Bauhaus is in the field of modern furniture design. The characteristic Cantilever chair and Wassily Chair designed by Marcel Breuer are two examples. (Breuer somewhen lost a legal battle in Germany with Dutch architect/designer Mart Stam over patent rights to the cantilever chair pattern. Although Stam had worked on the blueprint of the Bauhaus's 1923 showroom in Weimar, and guest-lectured at the Bauhaus later in the 1920s, he was non formally associated with the school, and he and Breuer had worked independently on the cantilever concept, leading to the patent dispute.) The nigh profitable production of the Bauhaus was its wallpaper.

The physical plant at Dessau survived World War II and was operated as a design school with some architectural facilities past the German Democratic Republic. This included live stage productions in the Bauhaus theater nether the name of Bauhausbühne ("Bauhaus Stage"). After German reunification, a reorganized school continued in the aforementioned building, with no essential continuity with the Bauhaus under Gropius in the early 1920s.[41] In 1979 Bauhaus-Dessau College started to organize postgraduate programs with participants from all over the world. This effort has been supported past the Bauhaus-Dessau Foundation which was founded in 1974 equally a public institution.

Afterwards evaluation of the Bauhaus design credo was critical of its flawed recognition of the human element, an acknowledgment of "the dated, unattractive aspects of the Bauhaus equally a project of utopia marked past mechanistic views of human nature…Home hygiene without dwelling house atmosphere."[42]

Subsequent examples which take continued the philosophy of the Bauhaus include Black Mountain Higher, Hochschule für Gestaltung in Ulm and Domaine de Boisbuchet.[43]

A Bauhaus-style edifice with "thermometer" windows on Pines Street in Tel Aviv

The White City [edit]

The White Urban center (Hebrew: העיר הלבנה, refers to a collection of over 4,000 buildings built in the Bauhaus or International Style in Tel Aviv from the 1930s past German Jewish architects who emigrated to the British Mandate of Palestine after the rise of the Nazis. Tel Aviv has the largest number of buildings in the Bauhaus/International Style of any city in the globe. Preservation, documentation, and exhibitions have brought attention to Tel Aviv's drove of 1930s compages. In 2003, the United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organization (UNESCO) proclaimed Tel Aviv's White Metropolis a Globe Cultural Heritage site, equally "an outstanding example of new town planning and compages in the early on 20th century."[44] The citation recognized the unique adaptation of modern international architectural trends to the cultural, climatic, and local traditions of the urban center. Bauhaus Center Tel Aviv organizes regular architectural tours of the city.

Centenary year, 2019 [edit]

As the centenary of the founding of Bauhaus, several events, festivals, and exhibitions were held around the world in 2019.[45] The international opening festival at the Berlin Academy of the Arts from 16 to 24 January concentrated on "the presentation and production of pieces by contemporary artists, in which the aesthetic issues and experimental configurations of the Bauhaus artists continue to be inspiringly contagious".[46] [47] Original Bauhaus, The Centenary Exhibition at the Berlinische Galerie (vi September 2019 to 27 January 2020) presented 1,000 original artefacts from the Bauhaus-Archiv'south collection and recounted the history behind the objects.[48]

2020, President of the European Committee Ursula Von der Leyen introduced the New European Bauhaus (NEB) initiative during her Country of the Union address. [edit]

In September 2020, President of the European Commission Ursula Von der Leyen introduced the New European Bauhaus (NEB) initiative during her State of the Wedlock address. The Neb is a creative and interdisciplinary motility that connects the European Green Deal to everyday life. It is a platform for experimentation aiming to unite citizens, experts, businesses and institutions in imagining and designing a sustainable, aesthetic and inclusive time to come.

2022 february, The New European Bauhaus: opportunities for the sport sector [edit]

Sport and physical activeness were an essential office of the original Bauhaus approach. Hannes Meyer, the second manager of Bauhaus Dessau, ensured that one twenty-four hour period a week was solely devoted to sport and gymnastics. ane In 1930, Meyer employed ii physical education teachers. The Bauhaus school even applied for public funds to enhance its playing field. The inclusion of sport and concrete action in the Bauhaus curriculum had various purposes. Starting time, as Meyer put it, sport combatted a "ane-sided accent on brainwork."[49] In improver, Bauhaus instructors believed that students could better express themselves if they actively experienced the space, rhythms and movements of the body. The Bauhaus approach also considered concrete activity an important contributor to wellbeing and customs spirit. Sport and physical action were essential to the interdisciplinary Bauhaus motion that developed revolutionary ideas and continues to shape our environments today.

Bauhaus staff and students [edit]

People who were educated, or who taught or worked in other capacities, at the Bauhaus.

Gallery [edit]

-

A stage in the Festsaal, Dessau

-

Ceiling with light fixtures for phase in the Festsaal, Dessau

-

Dormitory balconies in the residence, Dessau

-

Mechanically opened windows, Dessau

-

-

The Molitor Grapholux lamp, by Christian Dell (1922–25)

-

Clock designed by Erich Dieckmann (1931)

Encounter besides [edit]

- Fine art Deco architecture

- Bauhaus Archive

- Bauhaus Center Tel Aviv

- Bauhaus Dessau Foundation

- Bauhaus Museum, Tel Aviv

- Bauhaus Museum, Weimar

- Bauhaus Globe Heritage Site

- Constructivist architecture

- Expressionist compages

- Grade follows function

- Haus am Horn

- IIT Institute of Design

- International style (architecture)

- Max-Liebling House, Tel Aviv

- Modern compages

- Neues Sehen (New Vision)

- New Objectivity (architecture)

- Ulm School of Design

- Vkhutemas

- Women of the Bauhaus

Footnotes [edit]

- a The closure, and the response of Mies van der Rohe, is fully documented in Elaine Hochman's Architects of Fortune.

- Google honored Bauhaus for its 100th anniversary on 12 April 2019 with a Google Doodle.[50]

References [edit]

- ^ a b c d Oxford Dictionary of Art and Artists (Oxford: Oxford Academy Printing, quaternary edn., 2009), ISBN 0-19-953294-X, pp. 64–66

- ^ Pevsner, Nikolaus, ed. (1999). A Lexicon of Architecture and Mural Compages (Paperback). Fleming, John; Award, Hugh (5th ed.). London: Penguin Books. p. 880. ISBN978-0-14-051323-3.

- ^ "Bauhaus Movemen". Rethinking the world Fine art and Technology – A new Unity.

- ^ Barnes, Rachel (2001). The 20th-Century art book (Reprinted. ed.). London: Phaidon Press. ISBN978-0-7148-3542-6.

- ^ Evans, Richard J. The Coming of the Third Reich, p. 416

- ^ Funk and Wagnall'due south New Encyclopaedia, Vol 5, p. 348

- ^ a b (in Russian) Great Soviet Encyclopedia; Bolshaya Sovetskaya Entsiklopediya, Вхутемас

- ^ Wood, Paul (1999) The Challenge of the Avant-Garde. New Haven: Yale University Printing ISBN 0-300-07762-9, p. 244

- ^ Tony Fry (October 1999). A New Design Philosophy: An Introduction to Defuturing. UNSW Press. p. 161. ISBN978-0-86840-753-1 . Retrieved 15 May 2011.

- ^ Colton, Timothy J. (1995) Moscow: Governing the Socialist Metropolis. Cambridge MA: Harvard University Press ISBN 0-674-58749-nine; p. 215

- ^ Uhrig, Nicole (2020). Zukunftsfähige Perspektiven in der Landschaftsarchitektur für Gartenstädte: City – State – Life. Wiesbaden: Springer-Verlag. p. 113. ISBN978-three-658-28940-nine.

- ^ Gorman, Carma (2003). The Industrial Blueprint Reader. New York: Allworth Press. p. 98. ISBN1-58115-310-4.

- ^ Pevsner, Nikolaus, ed. (1999). A Dictionary of Architecture and Landscape Architecture (Paperback). Fleming, John; Laurels, Hugh (5th ed.). Penguin Books. p. 44. ISBN978-0-xix-860678-9.

- ^ a b Frampton, Kenneth (1992). "The Bauhaus: Evolution of an Thought 1919–32". Modern Architecture: A Critical History (3rd ed. rev. ed.). New York: Thames and Hudson, Inc. p. 124. ISBN978-0-500-20257-9.

- ^ Whitford, Frank, ed. (1992). The Bauhaus: Masters & Students by Themselves. London: Conran Octopus. p. 32. ISBN978-1-85029-415-iii.

He invented the proper noun 'Bauhaus' non only because it specifically referred to Bauen ('building', 'structure')—but too because of its similarity to the word Bauhütte, the medieval guild of builders and stonemasons out of which Freemasonry sprang. The Bauhaus was to be a kind of modern Bauhütte, therefore, in which craftsmen would piece of work on common projects together, the greatest of which would exist buildings in which the arts and crafts would be combined.

- ^ a b Hal Foster, ed. (2004). "1923: The Bauhaus … holds its first public exhibition in Weimar, Germany". Fine art Since 1900: Volume one – 1900 to 1944. Rosalind Krauss, Yve-Alain Bois, Benjamin Buchloh. New York: Thames & Hudson. pp. 185–189. ISBN978-0-500-28534-iii.

- ^ Curtis, William (1987). "Walter Gropius, German Expressionism, and the Bauhaus". Modernistic Architecture Since 1900 (2nd ed.). Prentice-Hall. pp. 309–316. ISBN978-0-xiii-586694-8.

- ^ "The Bauhaus, 1919–1933". The MET. The Metropolitan Museum of Art. Retrieved 14 June 2016.

- ^ "Bauhaus". Encyclopædia Britannica . Retrieved 14 June 2016.

- ^ Ackermann et al., Bauhaus (Cologne: Könemann, 1999), 406.

- ^ Michael Baumgartner and Josef Helfenstein At the Bauhaus in Weimar, 1921–1924 Archived 29 September 2009 at the Wayback Machine, at Zentrum Paul Klee

- ^ Magdalena Droste (2002) [1990] Bauhaus, 1919–1933 p. 113

- ^ Curtis, William (2000). "Walter Gropius, German Expressionism, and the Bauhaus". Modern Architecture Since 1900 (2nd ed.). Prentice-Hall. p. 120. ISBN978-0-13-586694-viii.

- ^ Richard A. Etlin (2002). Fine art, culture, and media under the 3rd Reich. University of Chicago Press. p. 291. ISBN978-0-226-22086-4 . Retrieved fifteen May 2011.

- ^ a b David Spaeth (1985). Ludwig Mies van der Rohe. Rizzoli New York. pp. 87–93. ISBN978-0-8478-0563-1.

- ^ Jardi, Enric (1991). Paul Klee. Rizzoli Intl Pubns, p. 22

- ^ , Richard J Evans, The 3rd Reich in Power, 325

- ^ Gropius, Walter (April 1919). "Manifesto of the Staatliches Bauhaus". BauhausManifesto.com.

- ^ "Unesco celebrates Tel Aviv". BBC News. viii June 2004. Retrieved 26 Apr 2010.

- ^ "White City of Tel-Aviv – the Modern Movement". whc.unesco.org.

- ^ Edward Lucie-Smith, Belatedly Modern: The Visual Arts Since 1945, London: Thames & Hudson, 1976, p. 164.

- ^ a b Gaston Diehl, Vasarely, New York: Crown, 1972, p. 12

- ^ Jean Luc Daval, History of Abstruse Painting, Paris: Hazan, 1989, p. 199.

- ^ Run into: William Chapin Seitz, Marla Price, Art in the Age of Aquarius, Smithsonian Inst Press, 1992, p. 92; Edward Lucie-Smith, Tardily Modern: The Visual Arts Since 1945, London: Thames & Hudson, 1976, p. 164; Jean Louis Ferrier, Yann Le Pichon, Art of our century: the story of western art, 1900 to the present 1990, London : Longman, p. 521.

- ^ Guitemie Maldonaldo, "Une réception différée et relayée. Fifty'Atelier d'art abstrait et le "modèle-Bauhaus", 1950–1953", in: Martin Schieder, Isabelle Ewig, In dice Freiheit geworfen: Positionen zur deutsch-französischen Kunstgeschichte nach 1945, Oldenbourg Verlag, 22 November 2006, p. 100.

- ^ Jean Louis Ferrier, Yann Le Pichon, Fine art of Our Century: The Story of Western Art, 1900 to the Present, 1990, London: Longman, p. 521.

- ^ Ulm, Ulmer Museum/HfG-Archiv. "HfG-Archiv Ulm – The HfG Ulm". www.hfg-archiv.ulm.de. Archived from the original on 4 October 2008. Retrieved 19 August 2008.

- ^ Bayer, H., Gropius, W., & Gropius, I. (Eds.). (1975). Bauhaus 1919–1928. London: Secker& Warburg.

- ^ Itten, J. (1963). Design and Form: The Bones Class at the Bauhaus and Afterward (Revised edition, 1975). New York: John Wiley & Sons.

- ^ O'Connor, Z. (2013). "The Shillito Design School: Australia'southward link with the Bauhaus". The International Journal of Pattern in Gild, half-dozen(3), 149–159.

- ^ "Bauhaus Dessau".

- ^ Schjeldahl, Peter, "Bauhaus Rules," The New Yorker, 16 November 2009

- ^ "Interview with Mathias Schwartz-Clauss, Boisbuchet´due south manager and program curator". Domaine de Boisbuchet. 13 June 2019. Retrieved 17 December 2019.

- ^ "UNESCO, Decision Text, World Heritage Centre, retrieved 14 September 2009".

- ^ Weber, Micholas Flim-flam, The Bauhaus at 100: scientific discipline by design, Nature, 6 Baronial 2019 (with pdf link)

- ^ "100 years Bauhaus: the opening festival". Retrieved 17 January 2019.

- ^ "Bauhaus in pictures: The architects exiled by Nazis". BBC News. sixteen January 2019. Archived from the original on 16 January 2019. Retrieved 17 January 2019.

- ^ "Original Bauhaus, The Centenary Exhibition". Berlinische Galerie. half dozen September 2019. Retrieved 16 September 2019.

- ^ "Concrete Education at The Bauhaus 1919 33 | PDF". Scribd . Retrieved 16 February 2022.

- ^ "100th Anniversary of Bauhaus". Google. 12 April 2019.

Bibliography [edit]

- Oskar Schlemmer (1972). Tut Schlemmer (ed.). The Letters and Diaries of Oskar Schlemmer . Translated by Krishna Winston. Wesleyan Academy Press. ISBN0-8195-4047-1.

- Stefan Boness (2012). Tel Aviv – The White Metropolis. Berlin: Jovis. ISBN978-iii-939633-75-4.

- Magdalena Droste, Peter Gossel, ed. (2005). Bauhaus. Taschen America LLC. ISBN3-8228-3649-iv.

- Marty Bax (1991). Bauhaus Lecture Notes 1930–1933. Theory and do of architectural training at the Bauhaus, based on the lecture notes fabricated by the Dutch ex-Bauhaus student and architect J.J. van der Linden of the Mies van der Rohe curriculum. Amsterdam: Architectura & Natura. ISBN90-71570-04-5.

- Anja Baumhoff (2001). The Gendered World of the Bauhaus. The Politics of Power at the Weimar Commonwealth's Premier Art Found, 1919–1931. Frankfurt, New York: Peter Lang. ISBN3-631-37945-v.

- Boris Friedewald (2009). Bauhaus. Munich, London, New York: Prestel. ISBN978-3-7913-4200-ix.

- Catherine Weill-Rochant (2008). Rita H. Gans (ed.). Bauhaus: Architektur in Tel Aviv (in French and German). Zurich: Kiriat Yearim.

- Catherine Weill-Rochant (April 2009). The Tel-Aviv School : a constrained rationalism. DOCOMOMO journal (Documentation and conservation of buildings, sites and neighbourhoods of the modern movement).

- Peder Anker (2010). From Bauhaus to Ecohouse: A History of Ecological Blueprint. LSU Printing. ISBN978-0-8071-3551-8.

- Kirsten Baumann (2007). Bauhaus Dessau: Architecture Design Concept. Berlin: JOVIS Verlag. ISBN978-three-939633-11-2.

- Monika Markgraf, ed. (2007). Archaeology of Modernism: Renovation Bauhaus Dessau. Berlin: JOVIS Verlag. ISBN978-3-936314-83-0.

- Torsten Blume / Burghard Duhm (Eds.) (2008). Bauhaus.Theatre.Dessau: Change of Scene. Berlin: JOVIS Verlag. ISBN978-3-936314-81-six.

- Eric Cimino (2003). Student Life at the Bauhaus, 1919–1933 (M.A.). Boston: UMass-Boston.

- Olaf Thormann: Bauhaus Saxony. arnoldsche Art Publishers 2019, ISBN 978-iii-89790-553-v.

External links [edit]

| | Wikimedia Commons has media related to Bauhaus. |

| | Look up Bauhaus in Wiktionary, the free dictionary. |

- Bauhaus Everywhere — Google Arts & Culture

- Bauhaus at Curlie

- "Germany celebrates the Bauhaus Centenary". Bauhaus Kooperation . Retrieved 28 March 2019.

- "100 years of Bauhaus". Bauhaus Kooperation . Retrieved 12 Apr 2019.

- "Glossary definition for Bauhaus}". Tate fine art . Retrieved 12 April 2019.

- Gropius, Walter. "Manifesto of the Staatliches Bauhaus". Design Museum of Chicago . Retrieved 12 April 2019.

- "Fostinum: Photographs and art from the Bauhaus". The Fostinum . Retrieved 12 April 2019.

- "Finding Aid for archive of Bauhaus student work, 1919–1933". J. Paul Getty Trust. hdl:10020/cifa850514. Retrieved 12 Apr 2019.

- "Finding Aid for annal of Bauhaus typography drove, 1919–1937". J. Paul Getty Trust. hdl:10020/cifa850513. Retrieved 12 Apr 2019.

- Collection: Artists of the Bauhaus from the University of Michigan Museum of Art

Source: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Bauhaus

0 Response to "The Was a German School of Art and Design That Operated in the Early Twentieth Century"

Post a Comment